I say all of this to set up the fact that Beatrix has little idea of how traditional TV works and seeing her first real exposure to it was enlightening to say the least.

One of the more limiting issues of writing client side script in the browser is the same origin limitations of XMLHttpRequest. The latest version of all browsers support a subset of CORS to allow servers to opt-in particular resources for cross-domain access. Since IE8 there's XDomainRequest and in all other browsers (including IE10) there's XHR L2's cross-origin request features. But the vast majority of resources out on the web do not opt-in using CORS headers and so client side only web apps like a podcast player or a feed reader aren't doable.

One hack-y way around this I've found is to use YQL as a CORS proxy. YQL applies the CORS header to all its responses and among its features it allows a caller to request an arbitrary XML, HTML, or JSON resource. So my network helper script first attempts to access a URI directly using XDomainRequest if that exists and XMLHttpRequest otherwise. If that fails it then tries to use XDR or XHR to access the URI via YQL. I wrap my URIs in the following manner, where type is either "html", "xml", or "json":

yqlRequest = function(uri, method, type, onComplete, onError) {

var yqlUri = "http://query.yahooapis.com/v1/public/yql?q=" +

encodeURIComponent("SELECT * FROM " + type + ' where url="' + encodeURIComponent(uri) + '"');

if (type == "html") {

yqlUri += encodeURIComponent(" and xpath='/*'");

}

else if (type == "json") {

yqlUri += "&callback=&format=json";

}

...

Anecdote on software usability. FTA: “… and suddenly realized that it was a perfectly ordinary whiteboard felt-tip pen. The headwaiter just draw an ”X” over their booking, directly on the computer screen!”

(via “What’s the waiter doing with the computer screen?” (javlaskitsystem.se))

Implied HTML elements, CSS before/after content, and the link HTTP header combines to make a document that displays something despite having a 0 byte HTML file. Demo only in Opera/FireFox due to link HTTP header support.

As a professional URI aficionado I deal with various levels of ignorance on URI percent-encoding (aka URI encoding, or URL escaping).

Getting into the more subtle levels of URI percent-encoding ignorance, folks try to apply their knowledge of percent-encoding to URIs as a whole producing the concepts escaped URIs and unescaped URIs. However there are no such things - URIs themselves aren't percent-encoded or decoded but rather contain characters that are percent-encoded or decoded. Applying percent-encoding or decoding to a URI as a whole produces a new and non-equivalent URI.

Instead of lingering on the incorrect concepts we'll just cover the correct ones: there's raw unencoded data, non-normal form URIs and normal form URIs. For example:

In the above (A) is not an 'encoded URI' but rather a non-normal form URI. The characters of 'the' and 'path' are percent-encoded but as unreserved characters specific in the RFC should not be encoded. In the normal form of the URI (B) the characters are decoded. But (B) is not a 'decoded URI' -- it still has an encoded '?' in it because that's a reserved character which by the RFC holds different meaning when appearing decoded versus encoded. Specifically in this case, it appears encoded which means it is data -- a literal '?' that appears as part of the path segment. This is as opposed to the decoded '?' that appears in the URI which is not part of the path but rather the delimiter to the query.

Usually when developers talk about decoding the URI what they really want is the raw data from the URI. The raw decoded data is (C) above. The only thing to note beyond what's covered already is that to obtain the decoded data one must parse the URI before percent decoding all percent-encoded octets.

Of course the exception here is when a URI is the raw data. In this case you must percent-encode the URI to have it appear in another URI. More on percent-encoding while constructing URIs later.

Sarah and I have been enjoying Glitch for a while now. Reviews are usually positive although occasionally biting (but mostly accurate).

I enjoy Glitch as a game of exploration: exploring the game's lands with hidden and secret rooms, and exploring the games skills and game mechanics. The issue with my enjoyment coming from exploration is that after I've explored all streets and learned all skills I've got nothing left to do. But I've found that even after that I can have fun writing client side JavaScript against Glitch's web APIs making tools (I work on the Glitch Helperator) for use in Glitch. And on a semi-regular basis they add new features reviving my interest in the game itself.

What Target discovered fairly quickly is that it creeped people out that the company knew about their pregnancies in advance.

“If we send someone a catalog and say, ‘Congratulations on your first child!’ and they’ve never told us they’re pregnant, that’s going to make some people uncomfortable,” Pole told me. “We are very conservative about compliance with all privacy laws. But even if you’re following the law, you can do things where people get queasy.”

As a professional URI aficionado I deal with various levels of ignorance on URI percent-encoding (aka URI encoding, or URL escaping).

Worse than the lame blog comments hating on percent-encoding is the shipping code which can do actual damage. In one very large project I won't name, I've fixed code that decodes all percent-encoded octets in a URI in order to get rid of pesky percents before calling ShellExecute. An unnamed developer with similar intent but clearly much craftier did the same thing in a loop until the string's length stopped changing. As it turns out percent-encoding serves a purpose and can't just be removed arbitrarily.

Percent-encoding exists so that one can represent data in a URI that would otherwise not be allowed or would be interpretted as a delimiter instead of data. For example, the space character (U+0020) is not allowed in a URI and so must be percent-encoded in order to appear in a URI:

http://example.com/the%20path/

http://example.com/the path/

For an additional example, the question mark delimits the path from the query. If one wanted the question mark to appear as part of the path rather than delimit the path from the query, it must be percent-encoded:

http://example.com/foo%3Fbar

http://example.com/foo?bar

/foo" from the query "bar". And in the first, the querstion mark is percent-encoded and so

the path is "/foo%3Fbar".

Awesome faux trailer for Psychonauts as Inception. Wish I had made the connection before - there’s a ton of overlap.

INCEPTIONAUTS (by FineLeatherJackets)

Most existing DRM attempts to only allow the user to access the DRM'ed content with particular applications or with particular credentials so that if the file is shared it won't be useful to others. A better solution is to encode any of the user's horrible secrets into unique versions of the DRM'ed content so that the user won't want to share it. Entangle the users and the content provider's secrets together in one document and accordingly their interests. I call this Blackmail DRM. For an implementation it is important to point out that the user's horrible secret doesn't need to be verified as accurate, but merely verified as believable.

Apparently I need to get these blog posts written faster because only recently I read about Social DRM which is a light weight version of my idea but with a misleading name. Instead of horrible secrets, they say they'll use personal information like the user's name in the DRM'ed content. More of my thoughts stolen and before I even had a chance to think of it first!

This is a great screenshot for IT departments to display at new employee orientation (via FAIL Nation: Probably Bad News: loln00bs)

As a professional URI aficionado I deal with various levels of ignorance on URI percent-encoding (aka URI encoding, or URL escaping). The basest ignorance is with respect to the mere existence of percent-encoding. Percents in URIs are special: they always represent the start of a percent-encoded octet. That is to say, a percent is always followed by two hex digits that represents a value between 0 and 255 and doesn't show up in a URI otherwise.

The IPv6 textual syntax for scoped addresses uses the '%' to delimit the zone ID from the rest of the address. When it came time to define how to represent scoped IPv6 addresses in URIs there were two camps: Folks who wanted to use the IPv6 format as is in the URI, and those who wanted to encode or replace the '%' with a different character. The resulting thread was more lively than what shows up on the IETF URI discussion mailing list. Ultimately we went with a percent-encoded '%' which means the percent maintains its special status and singular purpose.

“He’s either a bro or a hipster, he can’t be both. Because that’s not how stereotypes work.”

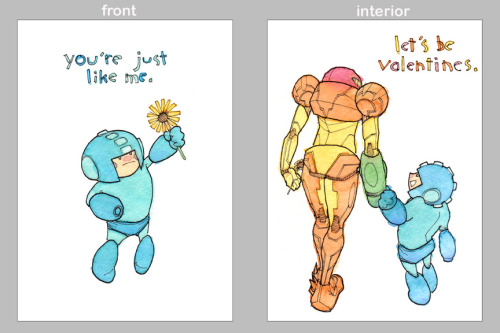

I made this Classic NES Valentine’s Card (free download in comments). - Imgur